Customers and employees: a new alliance?

Each company is a social contract between four types of stakeholders: employees, customers, shareholders and managers. Throughout history there have been different kinds of alliances between these stakeholders to capture the value created. Sometimes managers and shareholders together have organised their power to take the lion share. During other periods, managers have formed an alliance with employees to reap most of the benefits. In fact, to question the purpose of the company is to question the nature of this corporate contract. Does the company exist to create value for its customers, its shareholders, or its managers and employees?

Depending on negotiating power and market forces, employees and customers have often (schizophrenically) been opposed. Either employees are meant to create value for the company’s customers or customers must be made to pay for the employees’ jobs. Low prices often go hand in hand with low wages. The increased purchasing power that empowers the consumer is supposed to compensate for the lower wages that the employee must make do with. Conversely, as Ford saw it, richer employees can become new customers: focus on them and the rest will follow. Ford’s employees naturally created new outlets for the company’s products.

Should a manager focus on customers first and employees second? Or the other way around? It’s sometimes been said that happily empowered employees make for satisfied customers. Others argue that a strong customer-focused corporate vision gives employees a purpose and make for a strong culture. So when a company aims to improve the quality of its customer experience, where should it start? Let’s go over some of the ways this question has been answered…

Make the customer the focus of your corporate culture

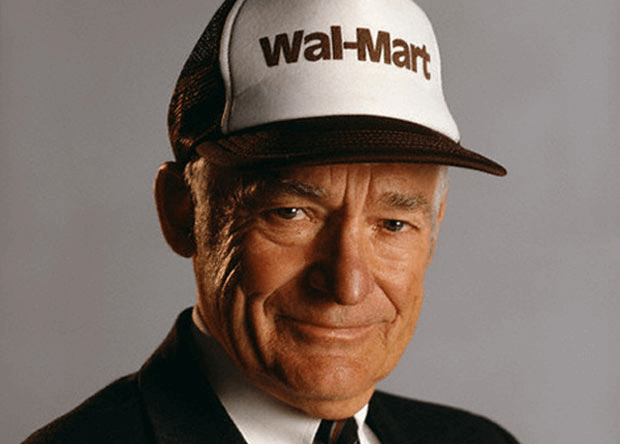

Numerous companies claim customer-centricity is at the heart of their corporate culture and mission. Yet very few actually embody customer-centricity so wholly as Walmart and Amazon. In fact, in both cases customer-centricity was the mission from the start. Everything else followed. Their accomplishment makes one wonder if customer-centricity can become your mission if it wasn’t at the origin. In Walmart’s and Amazon’s cases, it is ingrained in the corporate DNA: every infrastructure, every hire and every decision was made in accordance with it…

Its impact on society and economy cannot be overstated: Walmart generated a massive consumer surplus. In the Walmart age, badly-paid employees maintained their purchasing power (i.e. their relative wealth) only thanks to this consumer surplus: they could consume as much (or more) thanks to Walmart. Employees didn’t have to be encouraged to buy at Walmart, they just couldn’t shop anywhere else. Whereas Henry Ford gave his employees high wages so they could buy his cars, Sam Walton offered the lowest prices and his employees just had to buy his products. It is only because they were also consumers that employees could reap some of the value created by the company.

About a decade ago Walmart changed its slogan to “Save Money. Live Better”. Though the company can still be said to be customer-centric, it clearly revised its original mission to incorporate other values, and challenge the assumption that it created a world of impoverished workers. The wages of millions of Walmart employees have recently been increased — the increase may be modest, but when multiplied by millions, it isn’t neutral! The age of mass consumption may be coming to an end, so the original value-sharing scheme focused on consumer surplus may have reached certain limits.

Amazon: do more for the customer, not less

The media like to report on today’s “clash of titans” between Walmart and Amazon. But the truth is that the companies have a lot in common. They just happen to be separated by one generation. Like Walmart a generation before, Amazon’s very DNA can also be defined by its strict customer-centricity. CEO Jeff Bezos always insists he is obsessed with his customers. Employees are empowered to “act like owners” in the pursuit of that customer-centricity.

By heeding its customers, Amazon built all its platforms, including its successful Amazon Web Services (AWS) business. As a data-driven company from the start, Amazon has used its unprecedented knowledge of consumers to satisfy them better, create new products and services that they couldn’t have imagined possible. Not only can Amazon offer them the “lowest prices” by opening up its platform to all sellers and by creating the best technical and logistical operations, it can also offer them products and convenient services that they can’t find anywhere else.

Amazon always prides itself on not creating value for its shareholders. Its customer-centricity is the cement of its strong (and somewhat controversial) culture: every employee must understand that he / she exists only to serve customers. Shareholders, employees and managers can never come first. Every new technology or innovation makes it possible to do more for the customer, not just with lower prices (although prices matter too), but also with better services. Why make do with same-day deliveries if you can promise same-hour delivery? In many ways, Amazon has perfected the concept of consumer surplus so that it encapsulates more than just price.

Make your employees whole … and they will serve your customers better

Walmart and Amazon have long been controversial companies partly for the same reason: they both have hegemonic ambitions (create the biggest retail empire) that subordinate every other stakeholder to the customer. The customer-first-everybody-else-second approach becomes contentious when the company becomes successful… as some of the other stakeholders want a bigger piece of the cake too. Also, the success of a customer-centric approach (like Walmart’s) can be said to depend on national culture: what worked in the USA can not always be replicated elsewhere, as Walmart discovered when it tried and failed to “paste” the approach onto the German market (it turns out German employees did not like Walmart’s motivational songs).

Other leaders argue that an employee-first approach can in fact benefit the customers more in the end. A lot of today’s managerial debates focus on the idea that employees should be made whole…to create more value for the company, and that only a culture that cares for its employees can generate a culture that cares for its customers. In other words, employees that are miserable will not treat customers well. The idea isn’t new of course. It was at the heart of every successful paternalistic system. Today, it is better expressed in the idea that employees should be empowered to act with more autonomy, responsibility and creativity in increasingly “liberated” companies.

Employees and customers: a new alliance ?

Throughout the history of the Fordist economy, the enrichment of employees and customers have long been mutually exclusive, forcing a schizophrenic vision of the employee/consumer. At a time when workers had a strong negotiating power (with strong unions), roughly from the 1940s to the 1970s, employees could negotiate higher wages, mostly at the expense of consumers, and so prices weren’t low. When consumers started gaining more power (starting in the 1960s with new consumer movements), and when discount retail became common, it was at the expense of employee wages. Whereas General Motors paid its employees generous wages and pensions, Walmart does not.

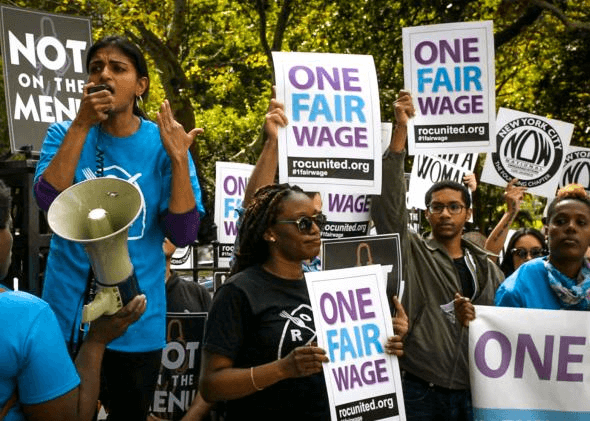

But in today’s digital economy, new models have emerged that allow for a new alliance between employees and customers. As union power has waned over the past four decades, most workers have seen their relative revenues decrease over the years. For the first time in a long time, some of these workers have succeeded in regaining some of their lost power, with the support of their companies’ customers. Unlike traditional unions, today’s movements are successful when (and only when) they raise enough awareness to obtain the support of the customers. The awareness campaigns of the “Fightfor15” campaign (“Fightfor15” is the movement that fights for a 15-dollar-an-hour minimum wage) is a case in point: although it faces difficult challenges today as some republican states have (momentarily?) defeated it, it can be credited for small victories in a lot of US states. In 2015–2016 the lowest wages of the unorganised workers have increased in the US.

Janitors and waitresses who work nights, home workers who drive alone and virtual workers who never leave home have no history of organising. The more disparate the group, the more challenging it is to foster solidarity. The more unequal and unevenly distributed the work schedules, the harder it is to organise. But technology proves helpful when atomised workers start to effectively use tools that allow them to connect and compare notes. “When couriers for the UberEats food delivery service went on wildcat strikes this summer, they communicated and co-ordinated through a private instant message group they all accessed on their phones” (Financial Times). Many activists are only now exploring how best to deploy technology to help them win new battles. And there are abundant tools to achieve that. (See O’Reilly’s report on Serving Workers in the Gig Economy.)

A movement like ROC United has successfully tested a form of alliance between employees and customers. The Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (ROC) is a not-for-profit organization and worker center with affiliates in a number of cities across the United States. Its mission is to improve wages and working conditions for the nation’s low wage restaurant workforce. Its tactics and strategy have drawn fire from business groups and restaurant industry lobbyists, but it has explored new ways to raise awareness with significant success. With social media, they have reached their goals faster and more effectively than a traditional union would have in this case.

In our digital age customer satisfaction can no longer be seen as a mere side benefit. It seems that today’s employees can no longer afford to argue for their interests if it means customer satisfaction might be degraded. That is largely the reason why traditional unions are becoming less and less relevant. Today’s most effective movements are digital-age lobbying organisations that rely on a new alliance between employees and customers. In many ways, this alliance is only in its infancy. It can be expected to gain momentum in the coming years.